Usefulness “Extremely Limited.” About that Florida Charter School Report…

On March 25, 2019, the Florida Department of Education celebrated the release of its annual charter school performance report with a press release titled: “New Report Finds Florida Charter School Students Consistently Outperform Their Peers in Traditional Public Schools.” Once again, the annual report failed to consider significant variables, like the socioeconomic effects on student performance, which may very well account for the study’s results. Once again, the Department of Education was caught deliberately ignoring well known analytical tools, creating a report that furthers a narrative rather than attempting to elicit the truth.

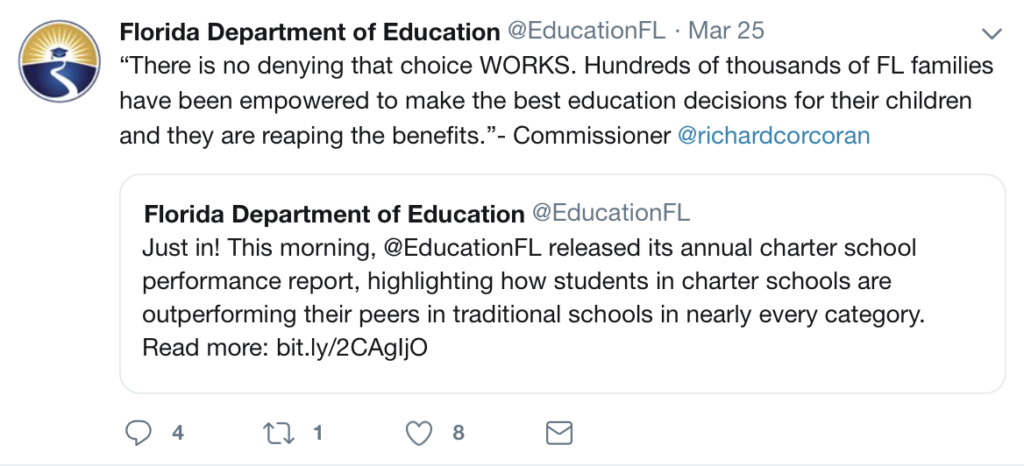

This year, under the leadership of Commissioner Richard Corcoran, the celebration was over the top:

Just in case you were wondering if there was any political motivation behind the reports, Corcoran went on to suggest: “Governor DeSantis has made bold choice-related proposals leading into the 2019 Legislative Session, and this report provides further evidence that they are right for Florida.”

Today, the National Education Policy Center (NEPC) published a review of Florida’s 2019 report, written by Syracuse University professor, Robert Bifulco. His review focuses largely on “the implications that should not be drawn from the report—but which policymakers and the public might be tempted to assume.” Such assumption, of course have already been made, and celebrated by school choice advocates across Florida. He concludes “clearly, the usefulness of this report for guiding policy and practice is extremely limited” and suggests it “encourages simplistic and potentially harmful conclusions.” The review’s summary reads:

“In March 2019, the Florida Department of Education published a report titled Student Achievement in Florida’s Charter Schools. The report consists almost entirely of simple graphs comparing achievement levels, achievement gaps, and achievement gains on statewide tests among charter school students to those among traditional public school students. Beyond the odd exercise of counting the number of comparisons that appear favorable to charter schools, the report offers no discussion. The comparisons are not even explained. The fact that the report merely presents comparisons required by law without putting any policy “spin” on them might be considered a virtue. The danger is that the report might encourage erroneous conclusions. The simple comparisons reveal very little about the relative effectiveness of charter schools and still less about other policy questions. At the very least, the report should have clarified the purposes of its comparisons and cautioned the reader against drawing unwarranted conclusions.”

Take a closer look at some of the review’s “Review of the Validity of the Findings and Conclusions”:

It might be viewed as a virtue of this report that it does not try to put any “spin” on the comparisons presented by drawing policy conclusions. Rather, it merely presents the comparisons required by legislation and leaves it to the reader to draw conclusions. What could be more transparent? The danger is that some readers might be tempted to draw erroneous conclusions from these comparisons or to use them to support predetermined political positions.

For instance, some might be persuaded that these comparisons provide evidence that charter schools are more effective than traditional public schools. However, among people familiar with program evaluation, it almost goes without saying that charter school students are likely to differ from traditional public school students in many ways other than their state test scores. In fact, a table provided at the beginning of the report suggests charter school students are less likely to be classified as eligible for free or reduced-priced lunch, as English language learners, or as having disabilities. They are also more likely to identify as Hispanic. These and many other differences between charter school students and traditional public school students are as likely to account for differences in achievement as any difference in the effectiveness of charter schools relative to traditional public schools.

This point is crucially important even when considering comparisons of charter school and traditional public schools within subgroups. We know that not all Black or Hispanic students are the same. Nor are all free-lunch eligible students or English language learners the same. Within any group, some students have greater academic ability, are more motivated, or have more parental support than other students in that group. If we believe either high- or low-ability students are more likely to see charter schools as an attractive alternative to their traditional public school, then we cannot draw any conclusions about the relative effectiveness of charter schools from simple comparisons within subgroups.

https://nepc.colorado.edu/sites/default/files/reviews/TTR%20Bifulco.pdf

We encourage you to read the entire review (here) and question why Florida tax dollars continue to be spent producing low quality annual reports with limited usefulness for guiding education policy and practice? Is the goal to encourage jumping to unwarranted conclusions or does anyone left at the FLDOE even care about determining how and when school choice options are actually effective?

One Comment