Understanding the Complexities of the FEFP

The Florida Education Finance Program, commonly referred to as the FEFP, is a complicated formula that strives to distribute education funding equitably across Florida’s diverse school districts. This blog is our attempt to explain this complex formula in basic terms so that we can discuss how components of SB7070 might impact funding through the formula. If you want to take a deeper dive into the FEFP, we recommend starting here, here and/or here.

SB7070, the Senate’s Education Train bill, calls for moving the funding for their newly revised Best and Brightest Teacher/Principal Bonus program into the Florida Education Finance Program or FEFP. It also calls for the elimination of the current School of Hope Program for Traditional Public Schools, which was funded outside the FEFP, and replacing it with a new program, funded via a new “Turnaround Schools Supplemental Services Allocation” within the FEFP. Finally, SB7070 also calls for the creation of a new private school voucher program aimed at eliminating the waitlist for the current Florida Tax Credit Scholarship (FTCS), which is funded by the diversion of corporate taxes. This new voucher, called the “Family Empowerment Scholarship” (FES), will ALSO be funded through the FEFP.

What is this FEFP and what will be the impacts of placing three new programs in it?

According to Senate Education Chair, Manny Diaz and Vice-Chair Bill Montford, the FEFP is a complex formula. Senator Diaz said “it was designed to send the money down from the state and the local funds collected to educate each child, individually, at an average of $7,407, I believe, it is this year, that is for the use of that child for this year.”

Sort of… Let’s learn little bit about this funding formula.

The Florida Education Finance Program

The FEFP was enacted by the 1973 Florida Legislature. It was established:

“To guarantee to each student in the Florida public education system the availability of programs and services appropriate to his educational needs which are substantially equal to those available to any similar student notwithstanding geographic differences and varying local economic factors.”

Through the FEFP, district funding is based on individual students and the programs in which they are participating. The program recognizes variations in local property tax bases, education program costs, costs of living and effects of population density/sparsity. A+ School Recognition Funds (paid for by Lottery funds) and Class Size Reduction (General Budget allocation) are also distributed to districts via the FEFP.

Part of the FEFP is funded by local property taxes through a calculation called the Required Local Effort. In districts that are “property rich,” local property owners are asked to generate as much as 90% of their district’s FEFP funding (with the State chipping in the final 10%). In districts with lower property tax bases, the State contributes a larger percentage of the FEFP. The formula’s goal is equitable funding and the formula, though complex, has withstood court challenges, earns high marks (for equity) and is often cited as a national model for funding equity.

The FEFP only includes funds for operations (NOT school construction). Also, the FEFP does NOT represent all of the funding that will support a district’s operations. Some programs and services (like the current Best and Brightest Teacher Bonus Program and the Gardiner ESA Scholarship for children with special needs, for example) are funded separately from the FEFP. Districts also receive federal funds separately.

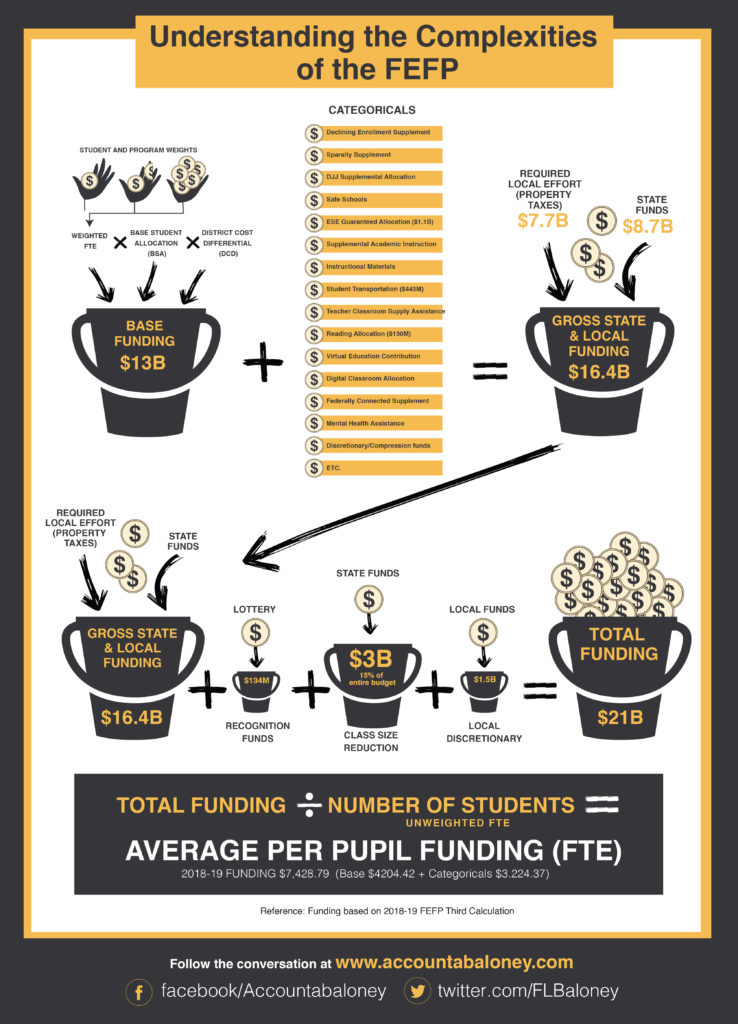

The concept of the FEFP is simple, although, in practice, the formula is quite complex. Basically, each year the legislature (via the budgeting process) determines the Base Student Allocation (BSA), this represents the district’s flexible funding and is used for salaries, toilet paper, air conditioning, etc. The BSA is multiplied by the Weighted FTE, which reflects both the number of students and their specific needs (see below), and adjusted for cost of living variations (via the District Cost Differential, or DCD). The result is the District’s “Base Funding.”

Added to the Base Funding are various “buckets of money,” called “categoricals,” which are supplemental funding for specific purposes, like transportation, mental health, safe schools or digital classroom plans. Some supplements adjust for regional differences like sparsely populated regions or those with declining enrollment. The result of adding the base funding and all of the categoricals is the “Gross State and Local FEFP”; this is the “pot of money” that is funded, in part, by the Required Local Effort, i.e. your property taxes.

When you add Lottery-funded School Recognition/A+ funds ($134.5 million in 2018-19) and Class Size Reduction Funds (over $3 Billion in 2018-19), along with some Discretionary Local Effort funds (additional, non-voted property tax for local discretionary use, levied by the district), the result is the Total State and Local Funding. If you divide the Total State and Local Funding by the total number of students (the unweighted FTE, see below), you get the per pupil funding calculation, sometimes referred to as the FTE.

For 2018-19, the Total State and Local Funding for Florida was $21,059,308,344. Total number of students was 2,834,821.61. The resulting total Funding per student was 7,428.79. Of that, $4,204.42 came from the Base Student Allocation and the rest was from the various categoricals.

It is important to note that different districts will have different levels of categorical funding and different proportions of students with special needs/progam weights, resulting in varying levels of per pupil funding between districts. For example, in 2018-19, per pupil funding varied by almost $2,500 between the lowest (Marion) and the highest (Monroe) districts:

- Marion County: $7,122.60/student

- Seminole: $7,174,03/student

- Jefferson: $9,151.50/student

- Monroe: $9,593.69/student

Is this fair? Remember, this formula has been studied extensively, withstood court challenges, and is generally felt to the a national model for equitable funding.

Unweighted vs Weighted FTE

It is also important to understand that, within the FEFP, all students are not funded equally. The total student population is called the Unweighted Full Time Equivalent or Unweighted FTE. This simply refers to the number of students.

Some students have higher needs and/or need special programing. These special needs (for example a child with extensive medical needs) are given extra funds through “Program Weights.” For example a child with Level V ESE services (the highest level of need) gets a program weight of 5.642 where as a so-called “basic” child in middle school without special needs has a program weight of 1.000. This means the the Level V special needs student would be assigned 5.642 TIMES more funding than the basic middle school child. Supplements are also added for advanced classes (like AP, IB, and AICE) and Industry Certification Career and Professional AcademyPrograms.

The Weighted FTE is calculated from the number of students and their special needs. The Weighted FTE is higher than the total student count (Unweighted FTE or UFTE) because it accounts for both the number of students AND their needs; it reflects that the Level V student described above warrants over 5 1/2 times the funding of the basic student.

The Weighted FTE is used to calculate the district’s Base Funding (which is the district’s “flexible” funding for day-to-day operations and, importantly, salaries) but the Unweighted FTE is used to calculate the per pupil spending/FTE (which is merely the average spending per student in that district or state).

Potential Impact of SB7070

SB7070 calls for the addition of three new categoricals within the FEFP:

- Newly revised Best and Brightest Teacher/Principal Bonus program (previously funded by the State, outside of the FEFP): The Governor’s 2019 budget calls for $423 million to be funding in the new FEFP categorical.

- Turnaround Schools Supplemental Services Allocation (replacing the School of Hope Program for Traditional Public Schools, which was previously funded outside the FEFP). Plan calls for an allocation providing qualified schools with up to $500/FTE.

- Family Empowerment Scholarship (new private school voucher program aimed at eliminating the waitlist for the current Florida Tax Credit Scholarship). Plan call for 15,000 vouchers, costing just over $100 million.

If these three proposals are added to FEFP formula, they will add over half a billion dollars to the Total Funding calculation, resulting in a calculated increase of $175 per student (unweighted FTE). This seemingly generous increase in funding will have ZERO impact on the Base Funding calculation, the money that districts can use to enact innovative district level programing or raise employee salaries and/or benefits.

The new Best and Brightest will provide bonuses for some teachers and principals but bonuses are not equivalent to raises… for example, one cannot qualify for a mortgage on the basis of a bonus. Stakeholders (including superintendents, school boards, school administrators and teachers) are ALL asking for an increase in the Base Student Allocation, allowing them to impact salaries in order to address the growing need to recruit and retain highly effective educators and district staff. By tying the new bonuses to school grade calculations, it will be more difficult for teachers in high-needs schools to receive these bonuses and will focus even greater attention of school grades and test scores in all public schools.

The Turnaround Schools Supplemental Services Allocation will provide some much needed funding for wraparound services in struggling communities/schools. This targeted funding for a specific need for struggling schools within districts is probably well placed in the FEFP, as it attempts to provide equity for struggling schools. We are curious to see how this program evolves.

The Family Empowerment Scholarship will send $100 million from the FEFP to private, mostly religious schools. With the exception of the McKay voucher for students with special needs, Florida’s other voucher programs are funded outside the FEFP (Gardiner ESA) or by diverted taxes through a tax-credit scheme (Florida Tax Credit Scholarship and Hope Scholarship). Placing this new voucher inside the FEFP will require local property taxes to be directed to private, mostly religious schools, something the voters overwhelmingly voted against in 2012 (see Amendment 8: Religious Freedom) while giving local taxpayers the illusion that more of their money is going to their local public schools.

The placement of this new voucher in the FEFP is even controversial amongst Republican leadership. When SB707 was presented to the Senate Education Committee on March 6th, Senate President Pro Tempore, David Simmons suggested the new voucher should not be funded out of the FEFP, noting that a similar proposal was struck down as unconstitutional by the Florida Supreme Court in 2006. From the Tampa Bay Times:

“All we have to do is expand that system … within the corporate tax scholarship umbrella that already exists,” Simmons said. “It’s not essential to take it out of the (per-student allocation).”

Simmons said the state could give corporations tax credits in exchange for them directing their corporate income tax, insurance tax and others to the voucher fund, which is similar to how it is funded now. That way, the dollars would be dedicated to the program before they reach the state’s coffers and are set aside for schools.

Diaz said he is “not adverse” to the idea.

A Shell Game

Moving previously funded programs into the FEFP does (at least) two things:

-It shifts state funding of education towards local funding of education, putting a greater burden on the local tax payer.

-It boosts the calculated “per-pupil spending” with no real increase in overall education spending.

It is a shell game. Local taxpayers believe their schools are being better funded, when there may not be any real increase in education spending.

A great example of this was last year’s FEFP which celebrated a $101 increase in per pupil spending, as a result of increased funding to a few categoricals (primarily “Safe Schools”) with only a 47 cent increase in the Base Student Allocation (BSA). While the paper’s celebrated record student spending, the districts hands were tied with regards to how they could spend most of it.

We agree with Senator Simmons that the funding for the Family Empowerment Voucher should not be in the FEFP. We believe the Best and Brightest Bonus funding would better serve teachers and principals if it were used, instead, to fund increases in the Base Student Allocation. We will be watching to see how Senator Simmons’ plans for assisting struggling schools and communities.

We are tired of the shell game and wish Florida’s legislators would take seriously their paramount duty to to make adequate provision for the education of all of Florida’s children. In the face of a nation wide teaching shortage crisis, that means funding the BSA so that districts can have the flexibility to increase salaries.

4 Comments